Arc de Triomphe

| Arc de Triomphe | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| Alternative names | Arc de Triomphe de l'Étoile |

| General information | |

| Type | Triumphal arch |

| Architectural style | Neoclassicism |

| Location | Place Charles de Gaulle (formerly Place de l'Étoile) |

| Coordinates | 48°52′25.6″N 2°17′42.1″E / 48.873778°N 2.295028°E |

| Construction started | 15 August 1806[1] |

| Inaugurated | 29 July 1836[2] |

| Height | 50 m (164 ft) |

| Dimensions | |

| Other dimensions | Wide: 45 m (148 ft) Deep: 22 m (72 ft) |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect(s) | Jean Chalgrin Louis-Étienne Héricart de Thury |

The Arc de Triomphe de l'Étoile,[a] often called simply the Arc de Triomphe, is one of the most famous monuments in Paris, France, standing at the western end of the Champs-Élysées at the centre of Place Charles de Gaulle, formerly named Place de l'Étoile—the étoile or "star" of the juncture formed by its twelve radiating avenues. The location of the arc and the plaza is shared between three arrondissements, 16th (south and west), 17th (north), and 8th (east). The Arc de Triomphe honours those who fought and died for France in the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars, with the names of all French victories and generals inscribed on its inner and outer surfaces. Beneath its vault lies the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier from World War I.

The central cohesive element of the Axe historique (historic axis, a sequence of monuments and grand thoroughfares on a route running from the courtyard of the Louvre to the Grande Arche de la Défense), the Arc de Triomphe was designed by Jean Chalgrin in 1806; its iconographic programme pits heroically nude French youths against bearded Germanic warriors in chain mail. It set the tone for public monuments with triumphant patriotic messages. Inspired by the Arch of Titus in Rome, Italy, the Arc de Triomphe has an overall height of 50 m (164 ft), width of 45 m (148 ft) and depth of 22 m (72 ft), while its large vault is 29.19 m (95.8 ft) high and 14.62 m (48.0 ft) wide. The smaller transverse vaults are 18.68 m (61.3 ft) high and 8.44 m (27.7 ft) wide.

Paris's Arc de Triomphe was the tallest triumphal arch until the completion of the Monumento a la Revolución in Mexico City in 1938, which is 67 m (220 ft) high. The Arch of Triumph in Pyongyang, completed in 1982, is modeled on the Arc de Triomphe and is slightly taller at 60 m (197 ft). The Grande Arche in La Défense near Paris is 110 metres high, and, if considered to be a triumphal arch, is the world's tallest.[6]

History

Construction and late 19th century

The Arc de Triomphe is located on the right bank of the Seine at the centre of a dodecagonal configuration of twelve radiating avenues. It was commissioned in 1806, after the victory at Austerlitz by Emperor Napoleon at the peak of his fortunes. Laying the foundations alone took two years and, in 1810, when Napoleon entered Paris from the west with his new bride, Archduchess Marie-Louise of Austria, he had a wooden mock-up of the completed arch constructed. The architect, Jean Chalgrin, died in 1811 and the work was taken over by Jean-Nicolas Huyot.

During the Bourbon Restoration, construction was halted, and it would not be completed until the reign of Louis Philippe I, between 1833 and 1836, by the architects Goust, then Huyot, under the direction of Héricart de Thury. The final cost was reported at about 10,000,000 francs (equivalent to an estimated €65 million or $75 million in 2020).[7][8]

On 15 December 1840, brought back to France from Saint Helena, Napoleon's remains passed under it on their way to the Emperor's final resting place at Les Invalides.[9] Before burial in the Panthéon, the body of Victor Hugo was displayed under the Arc on the night of 22 May 1885.

-

The wooden Arc de Triomphe built on the occasion of the entry into Paris of Napoleon and Marie Louise in 1810

-

The Place de l'Étoile and Arc de Triomphe in 1857

-

View of the Arc de Triomphe after the Commune, by Franck, 1871

-

State funeral of Victor Hugo, 31 May 1885

20th century

The sword carried by the Republic in the Marseillaise relief broke off on the day, it is said, that the Battle of Verdun began in 1916. The relief was immediately hidden by tarpaulins to conceal the accident and avoid any undesired ominous interpretations.[10]

On 7 August 1919 three weeks after the Paris victory parade in 1919 (marking the end of hostilities in World War I), Charles Godefroy flew his Nieuport biplane under the arch's primary vault, with the event captured on newsreel.[11][12][13] Jean Navarre was the pilot who was tasked to make the flight, but he died on 10 July 1919 when he crashed near Villacoublay while training for the flight

Following its construction, the Arc de Triomphe became the rallying point of French troops parading after successful military campaigns and for the annual Bastille Day military parade. Famous victory marches around or under the Arc have included the Germans in 1871, the French in 1919, the Germans in 1940, and the French and Allies in 1944[14] and 1945. A United States postage stamp of 1945 shows the Arc de Triomphe in the background as victorious American troops march down the Champs-Élysées and U.S. airplanes fly overhead on 29 August 1944. After the interment of the Unknown Soldier, however, all military parades (including the aforementioned post-1919) have avoided marching through the actual arch. The route taken is up to the arch and then around its side, out of respect for the tomb and its symbolism. Both Hitler in 1940 and Charles de Gaulle in 1944 observed this custom.

By the early 1960s, the monument had grown very blackened from coal soot and automobile exhaust, and during 1965–1966 it was cleaned through bleaching. In the prolongation of the Avenue des Champs-Élysées, a new arch, the Grande Arche de la Défense, was built in 1982, completing the line of monuments that forms Paris's Axe historique. After the Arc de Triomphe du Carrousel and the Arc de Triomphe de l'Étoile, the Grande Arche is the third arch built on the same perspective.

In 1995, the Armed Islamic Group of Algeria placed a bomb near the Arc de Triomphe which wounded 17 people as part of a campaign of bombings.[15]

On 12 July 1998, when France won the FIFA World Cup for the first time after defeating Brazil 3–0 at the Stade de France, images of the players including double goal scorer Zinedine Zidane and their names along with celebratory messages were projected onto the arch.[16]

-

Charles Godefroy flying through the Arc de Triomphe in 1919

-

Arc de Triomphe, postcard, c. 1920

-

A colourized aerial photograph of the southern side, published in 1921

-

Arc de Triomphe in 1939

-

Free French forces on parade after the liberation of Paris on 26 August 1944

21st century

In late 2018, the Arc de Triomphe suffered acts of vandalism as part of the Yellow vests protests.[17] The vandals sprayed the monument with graffiti and ransacked its small museum.[18] In September 2021, the arc was wrapped in a silvery blue fabric and red rope,[19] as part of L'Arc de Triomphe, Wrapped, a posthumous project planned by artists Christo and Jeanne-Claude since the early 1960s.[20]

-

Night view of the Arc de Triomphe, 2007

-

The Arc de Triomphe seen from the Eiffel Tower, 2008

-

Laurent Fabius, Minister of Foreign Affairs, with John Kerry, U.S. Secretary of State, under the Arc de Triomphe in 2015

-

Bastille Day military parade, 2017

Design

Monument

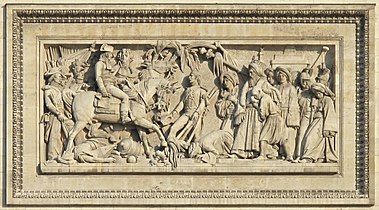

The astylar design is by Jean Chalgrin (1739–1811), in the Neoclassical version of ancient Roman architecture. Major academic sculptors of France are represented in the sculpture of the Arc de Triomphe: Jean-Pierre Cortot; François Rude; Antoine Étex; James Pradier and Philippe Joseph Henri Lemaire. The main sculptures are not integral friezes but are treated as independent trophies applied to the vast ashlar masonry masses, not unlike the gilt-bronze appliqués on Empire furniture. The four sculptural groups at the base of the Arc are The Triumph of 1810 (Cortot), Resistance and Peace (both by Antoine Étex), and the most renowned of them all, Departure of the Volunteers of 1792 commonly called La Marseillaise (François Rude). The face of the allegorical representation of France calling forth her people on this last was used as the belt buckle for the honorary rank of Marshal of France. Since the fall of Napoleon (1815), the sculpture representing Peace is interpreted as commemorating the Peace of 1815.[21]

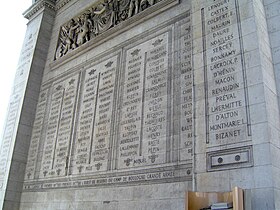

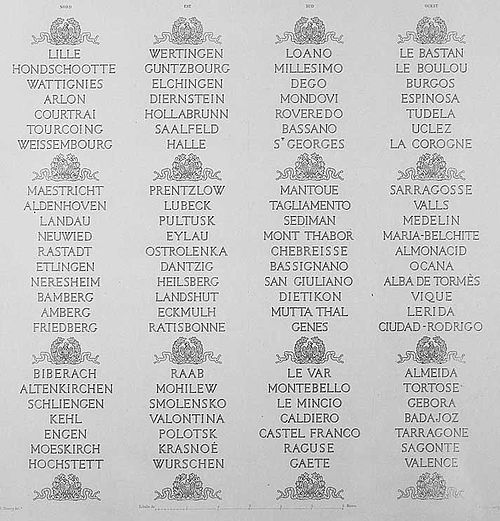

In the attic above the richly sculptured frieze of soldiers are 30 shields engraved with the names of major French victories in the French Revolution and Napoleonic wars.[22] The inside walls of the monument list the names of 660 people, among which are 558 French generals of the First French Empire;[23] The names of those generals killed in battle are underlined. Also inscribed, on the shorter sides of the four supporting columns, are the names of the major French victories in the Napoleonic Wars. The battles that took place in the period between the departure of Napoleon from Elba to his final defeat at Waterloo are not included.[24]

For four years from 1882 to 1886, a monumental sculpture by Alexandre Falguière topped the arch. Titled Le triomphe de la Révolution ("The Triumph of the Revolution"), it depicted a chariot drawn by horses preparing "to crush Anarchy and Despotism".[25]

Inside the monument, a permanent exhibition, conceived by artist Maurice Benayoun and architect Christophe Girault, opened in February 2007.[26]

Tomb of the Unknown Soldier

Beneath the Arc is the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier from World War I. Interred on Armistice Day 1920,[27] an eternal flame burns in memory of the dead who were never identified (now in both world wars).[28]

A ceremony is held at the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier every 11 November on the anniversary of the Armistice of 11 November 1918 signed by the Entente Powers and Germany in 1918. It was originally decided on 12 November 1919 to bury the unknown soldier's remains in the Panthéon, but a public letter-writing campaign led to the decision to bury him beneath the Arc de Triomphe. The coffin was put in the chapel on the first floor of the Arc on 10 November 1920, and put in its final resting place on 28 January 1921.[28] The slab on top bears the inscription: Ici repose un soldat français mort pour la Patrie, 1914–1918 ("Here rests a French soldier who died for the Fatherland, 1914–1918").[28]

In 1961, U.S. President John F. Kennedy and First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy paid their respects at the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier, accompanied by President Charles de Gaulle. After the 1963 assassination of President Kennedy, Mrs. Kennedy remembered the eternal flame at the Arc de Triomphe and requested that an eternal flame be placed next to her husband's grave at Arlington National Cemetery in Virginia.[29]

Details

- The four main sculptural groups on each of the Arc's pillars are:

- Le Départ de 1792 (or La Marseillaise), by François Rude. The sculptural group celebrates the cause of the French First Republic during the 10 August uprising. Above the volunteers is the winged personification of Liberty. This group served as a recruitment tool in the early months of World War I and encouraged the French to invest in war loans in 1915–1916.[30]

- Le Triomphe de 1810, by Jean-Pierre Cortot celebrates the Treaty of Schönbrunn. This group features Napoleon, crowned by the goddess of Victory.

- La Résistance de 1814, by Antoine Étex commemorates the French Resistance to the Allied Armies during the War of the Sixth Coalition.

- La Paix de 1815, by Antoine Étex commemorates the Treaty of Paris, concluded in that year.

-

Le Départ de 1792

(La Marseillaise). -

Le Triomphe de 1810.

-

La Résistance de 1814.

-

La Paix de 1815.

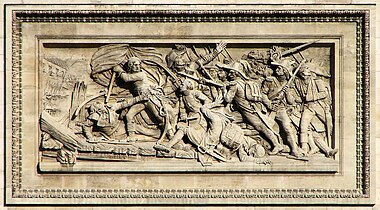

- Six reliefs sculpted on the façades of the Arch, representing important moments of the French Revolution and of the Napoleonic era include:

- Les funérailles du général Marceau (General Marceau's burial), by Philippe Joseph Henri Lemaire (Southern façade, right).

- La bataille d'Aboukir (The Battle of Aboukir), by Bernard Seurre (Southern façade, left).

- La bataille de Jemappes (The Battle of Jemappes), by Carlo Marochetti (Eastern façade).

- Le passage du pont d'Arcole (The Battle of Arcole), by Jean-Jacques Feuchère (Northern façade, right).

- La prise d'Alexandrie (The Fall of Alexandria), by John-Étienne Chaponnière (Northern façade, left).

- La bataille d'Austerlitz (The Battle of Austerlitz), by Jean-François-Théodore Gechter (Western façade).

-

Les funérailles du général Marceau,

20 September 1796. -

La bataille d'Aboukir,

25 July 1799. -

La bataille de Jemmappes,

6 November 1792. -

Le passage du pont d'Arcole,

15 November 1796. -

La prise d'Alexandrie,

3 July 1798. -

La bataille d'Austerlitz,

2 December 1805.

- The names of 158 battles fought by the French First Republic and the First French Empire are engraved on the monument. Among them, 30 battles are engraved on the attic:

- 96 battles are engraved on the inner façades, under the great arches:

- The names of 660 military leaders who served during the French First Republic and the First French Empire are engraved on the inner façades of the small arches.[31][32] Underlined names signify those who died on the battlefield:

-

Northern pillar.

-

Eastern pillar.

-

Southern pillar.

-

Western pillar.

- The great arcades are decorated with allegorical figures representing characters in Roman mythology (by James Pradier):

- The ceiling with 21 sculpted roses:

- Interior of the Arc de Triomphe:

-

First World War monument.

-

Permanent exhibition about the design of the Arch.

- There are several plaques at the foot of the monument:

Access

The Arc de Triomphe is accessible by the RER and Métro, with exit at the Charles de Gaulle–Étoile station. Because of heavy traffic on the roundabout of which the Arc is the centre, pedestrians use the two underpasses located at the Champs-Élysées and the Avenue de la Grande Armée. A lift will take visitors almost to the top – to the attic, where a small museum contains large models of the Arc and tells its story from the time of its construction. Another 40 steps remain to climb to reach the top, the terrasse, from where one can enjoy a panoramic view of Paris.[33]

The location of the arc, as well as the Place de l'Étoile, is shared between three arrondissements, 16th (south and west), 17th (north), and 8th (east).

-

Paris seen from the top of the Arc de Triomphe.

Replicas

While many structures around the world resemble the Arc de Triomphe, some were actually inspired by it. Replicas that used its design as a model include Arch of Triumph in Pyongyang, North Korea; Arcul de Triumf in Bucharest, Romania; Rosedale World War I Memorial Arch in Kansas City, Kansas, US; and a miniature version at the Paris Casino in Las Vegas, US.[34]

See also

- Names inscribed under the Arc de Triomphe

- Battles inscribed on the Arc de Triomphe

- List of works by James Pradier

- Napoleon's tomb

- Galerie des Batailles

- Bastille Day military parade

- Romanian Arcul de Triumf

- List of tourist attractions in Paris

- List of post-Roman triumphal arches

Notes

- ^ UK: /ˌɑːrk də ˈtriːɒmf, - ˈtriːoʊmf/,[3][4] US: /- triːˈoʊmf/,[5] French: [aʁk də tʁijɔ̃f də letwal] ; lit. 'Triumphal Arch of the Star'

References

- ^ Raymond, Gino (30 October 2008). Historical dictionary of France. Scarecrow Press. p. 9. ISBN 978-0-8108-5095-8. Archived from the original on 12 January 2023. Retrieved 28 July 2011.

- ^ Fleischmann, Hector (1914). An unknown son of Napoleon. John Lane company. p. 204. Retrieved 28 July 2011.

- ^ "Arc de Triomphe". Lexico UK English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on 18 August 2020.

- ^ "Arc de Triomphe". Collins English Dictionary. HarperCollins. Archived from the original on 22 August 2019. Retrieved 22 August 2019.

- ^ "arc de triomphe". Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. Merriam-Webster. Retrieved 22 August 2019.

- ^ "Arc de Triomphe facts". Paris Digest. 2018. Archived from the original on 7 September 2018. Retrieved 6 September 2018.

- ^ L'Abeille (in French). Petit Séminaire de Québec. 1848. Archived from the original on 12 January 2023. Retrieved 25 November 2021.

- ^ "Historical Currency Converter". www.historicalstatistics.org. Archived from the original on 20 January 2016. Retrieved 5 October 2021.

- ^ Hôtel des Invalides website Archived 25 July 2008 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ "History of the Arc de Triomphe in Paris". Places in France. Archived from the original on 7 October 2012. Retrieved 28 December 2013.

- ^ "Les débuts de l'aviation : Charles Godefroy – L'Histoire par l'image". Histoire-image.org. Archived from the original on 10 August 2014. Retrieved 13 August 2014.

- ^ Melville Wallace, La vie d'un pilote de chasse en 1914–1918, Flammarion, Paris, 1978. The film clip is included in The History Channel's Four Years of Thunder.

- ^ * « Un aviateur passe en avion sous l'Arc de Triomphe » Archived 30 September 2020 at the Wayback Machine, Le Matin from 1919/08/08, p.1, column 3–4.

- « Un avion passe sous l'Arc de Triomphe » Archived 21 September 2020 at the Wayback Machine, L'Écho de Paris from 1919/08/08, p.1, column 3.

- « L'Acte insensé d'un aviateur » Archived 23 October 2020 at the Wayback Machine, par Raoul Alexandre, L'Humanité from 1919/08/08, p.1, column 2.

- « Un avion, ce matin, est passé sous l'Arc de Triomphe » Archived 21 September 2020 at the Wayback Machine, par Paul Cartoux, L'Intransigeant from 1919/08/08, p.1, column 6.

- « Aéronautique : l'inutile exploit du sergent Godefroy » Archived 28 October 2020 at the Wayback Machine, Le Temps from 1919/08/09, morning edition, p.3, column 4–5.

- ^ Image of Liberation of Paris parade Archived 28 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Simons, Marlise (18 August 1995). "Bomb Near Arc De Triomphe wounds 17". New York Times. Archived from the original on 8 January 2015. Retrieved 8 January 2015.

- ^ France 2 (13 July 1998). "France 98 : Nuit de fête sur les Champs-Elysées après la victoire (Archive INA)" [France 98: Night of celebration on the Champs-Elysées after the victory]. YouTube (in French). Institut National de l'Audiovisuel. Archived from the original on 20 July 2023. Retrieved 20 July 2023.

- ^ Irish, John (2 December 2018). "Macron mulls state of emergency after worst unrest in decades". Reuters. Archived from the original on 26 July 2020. Retrieved 2 December 2018.

- ^ Katz, Brigit. "Arc de Triomphe to Reopen After Being Vandalized During 'Yellow Vest' Protests". Smithsonian Magazine. Archived from the original on 6 February 2022. Retrieved 4 July 2020.

- ^ Chappell, Bill (17 September 2021). "Here's Why The Arc De Triomphe Was Just Wrapped In Fabric". NPR. Archived from the original on 19 September 2021. Retrieved 19 September 2021.

- ^ Katz, Brigit (13 June 2021). "L'Arc de Triomphe, Wrapped: Christo's dream being realised". TheGuardian.com. Archived from the original on 20 June 2021. Retrieved 21 June 2021.

- ^ "Sculpture on the Arc De Triomphe: the Peace of 1815 by Antoine Etex". Ackland Art Museum. Archived from the original on 12 January 2023. Retrieved 1 October 2022.

- ^ The Battle of Fuentes de Oñoro is inscribed as a French victory, instead of the tactical draw and strategic defeat that it actually was.

- ^ Among the generals are at least two foreign generals, Venezuelan Francisco de Miranda and German-born Nicolas Luckner.

- ^ "Discover the Arc de Triomphe in Paris". French Monuments. 26 November 2012. Archived from the original on 29 May 2022. Retrieved 29 May 2022.

- ^ L'Art moderne. Imp. Ve (i.e. 5th) Monnom. 1882. p. 318. Archived from the original on 20 November 2023. Retrieved 18 March 2023.

- ^ "Between War and Peace". Archived from the original on 16 December 2014. Retrieved 15 September 2014.

- ^ Naour, Jean-Yves Le; Allen, Penny (16 August 2005). The Living Unknown Soldier: A Story of Grief and the Great War. Macmillan. p. 74. ISBN 978-0-8050-7937-1. Retrieved 28 July 2011.

- ^ a b c Granfield, Linda (2008). The Unknown Soldier. North Winds Press. ISBN 978-0-4399-3558-6. Archived from the original on 20 November 2023. Retrieved 18 March 2023.

- ^ Gormley, Beatrice; Meryl Henderson (11 May 2010). Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis: Friend of the Arts. New York: Simon and Schuster. pp. 142–43. ISBN 978-1-4391-1358-5. Retrieved 1 August 2024.

- ^ Forrest, Alan (28 May 2009). The Legacy of the French Revolutionary Wars. Cambridge University Press. p. 38. ISBN 978-1-1394-8924-9.

- ^ Divry, Arnauld (2023). "Les 660 noms inscrits sur l'Arc de Triomphe de Paris". arnauld-divry.ovh. Retrieved 25 August 2024.

- ^ Baedeker, Karl (1860). Guide à Paris par Baedeker: Arc de Triomphe de l'Étoile. Paris: A. Bohné. p. 91. Archived from the original on 12 January 2023. Retrieved 13 August 2021.

- ^ "Offer to everyone the best view on Paris". Centre des Monuments Nationaux. Archived from the original on 17 February 2019. Retrieved 18 July 2019.

- ^ "These Arc de Triomphe Around the World… And in Montpellier?". La Comédie de Vanneau. 20 November 2020. Archived from the original on 21 April 2023. Retrieved 21 April 2023.

External links

- Arc de Triomphe

- Buildings and structures completed in 1836

- Monuments and memorials in Paris

- Neoclassical architecture in Paris

- Triumphal arches in France

- Buildings and structures in the 8th arrondissement of Paris

- Buildings and structures in the 16th arrondissement of Paris

- Buildings and structures in the 17th arrondissement of Paris

- Landmarks in France

- Champs-Élysées

- Terminating vistas in Paris

- Monuments of the Centre des monuments nationaux